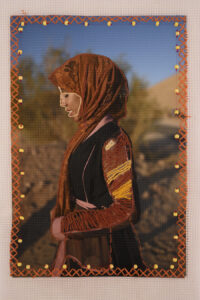

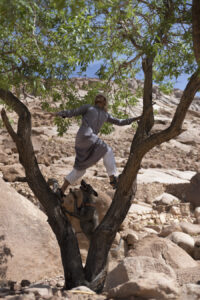

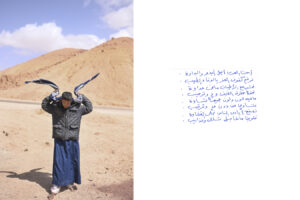

Over a span of 10 years, I collaborated with the Bedouin community of South Sinai, Egypt to explore the notion of belonging. The Bedouin community defines this notion through their intertwined attachment to land – they are its eternal keepers. The community are participants in the creative process, contributing with their traditional mediums such as embroidery and poetry. The result is a dance, a visual conversation on the continuous human process of searching for home and a celebration of the indigenous experience that has long been seen through a romanticized gaze. The final outcome is a complementary collection of photographs, written content, embroidered photographs on fabric and photographic paper, artifacts, sound and video.

I believe it’s a common human emotion to seek a definition of one’s identity, yet its complexity is often ignored, creating flattened labels and othering. The project challenges past colonial, orientalist and exotic narratives told of the Bedouins specifically and of the indigenous communities at large. It advocates for reshaping the representation of native and non-western communities in future narratives.

In its universal form, the project questions what it means to belong, what is this indescribable connection to the land that we all long for and the indigenous experience that is filled with both sorrow and celebration. It invites the audience to examine their own idea of belonging while acknowledging the community’s voice, consent and collaboration in the process.

In 2021, the Egyptian government launched a “new nation” project. Natural valleys have been paved, historical monuments demolished and native communities have been displaced including the Bedouin community of South Sinai. Since the government’s intrusion, concrete has been creeping over the mountainous land and many families have become homeless. The natural and cultural state of the land and its keepers – indigenous community – is under threat. This is when I decided to publish my book, for its urgency to document life before the big change and as a form of protest amid an oppressive regime.

The project is a contemporary Bedouin archive woven by the people themselves and my opportunity to reconnect to my indigenous Bedouin ancestry by collaborating with and learning from the existing community.