Seconded By: Lars Boering,

Rain Callers is a long term personal project capturing the practices of the Jarawi singers, who utilize polyphonic techniques to harmonize the agricultural cycle and heal the land from its drought.

Faced with the government neglect and irreparable damage from intense droughts that exacerbate poverty and social inequalities, the wise Quechua and Wanka women cantoras of the Jarawi gather to sing to the rain. Together, their voices perform the pre-Columbian verses that their grandmothers once recited when cultivating and harvesting the land. With polyphonic techniques to harmonize the agricultural cycle and heal the land from its drought. Seeking solutions within their own cosmovision.

This project is deeply rooted in my bond with my grandmother, a Quechua elder who once serenaded me with a special song: the Jarawi—a pre-Columbian verse preserved within her community in Huancavelica, nestled in the Peruvian Andes. These Quechua verses, performed to beckon the rain, embody the language of nature itself—the Jarawi is a timeless dialogue with the Earth.

“We plant the seeds with the power of the song”, shares Magdalena Gamboa, a wise elder of the Wanka people.

While the community starts planting corn seeds, Magdalena, Elvia and Graciela, cantoras of the Jarawi gather to sing to the rain and call it. Together, their voices perform the pre-columbian verses that their ancestors used to recite, unveiling their resilient responses to heat and drought, bringing ancient indigenous practices to face current climate issues.

This series weaves my own voice and memory into the story, using my grandmother’s voice, memory and archive as a central thread to explore the resilience of Quechua-Wanka women. Through their poetry, symbolism, and powerful imagery, it reveals their unique way of healing our precious Earth.

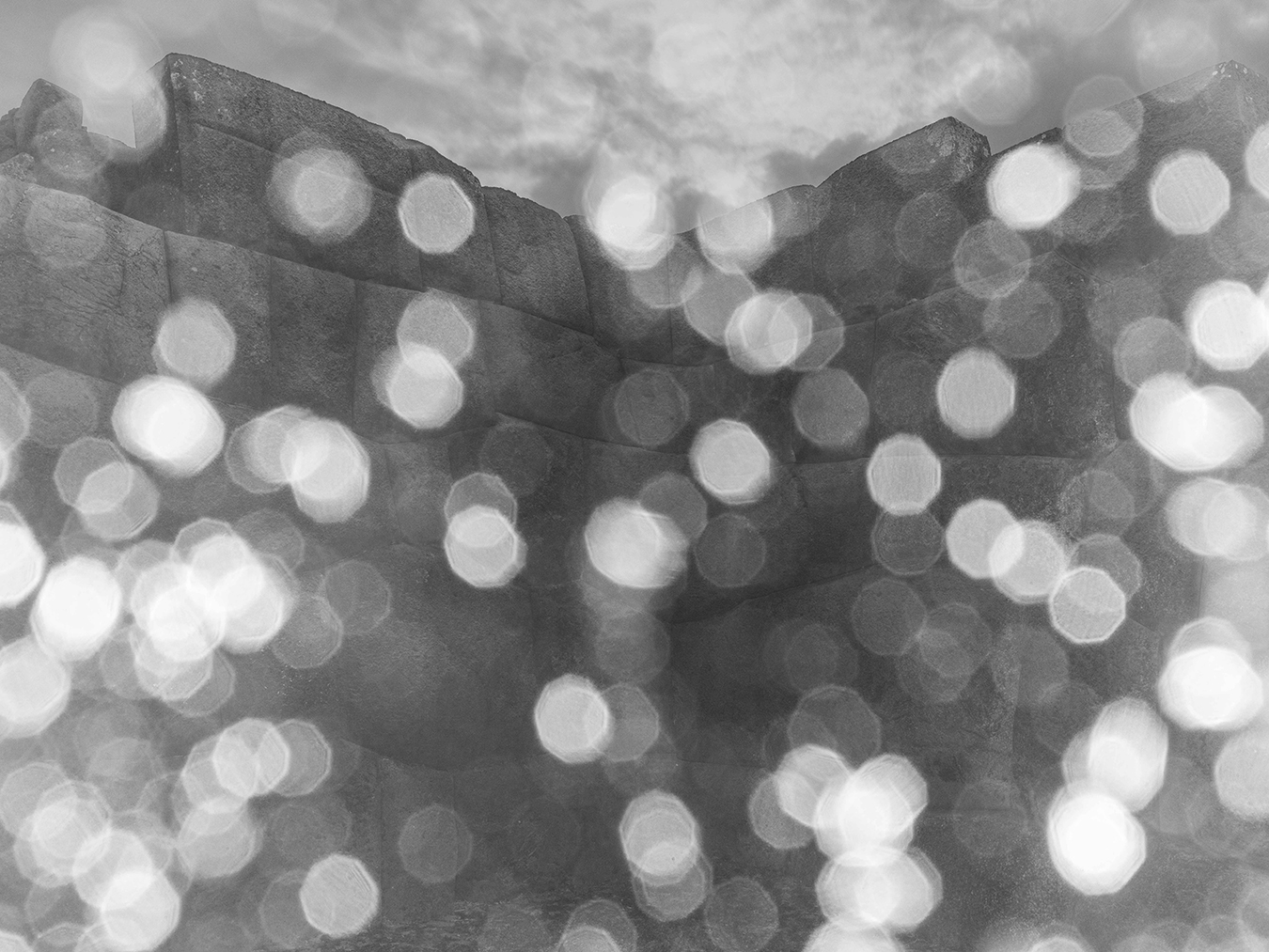

A family archive photo taken by my grandmother in the 1970s, marked by white specks—like drops of rainwater—from the passage of time. My uncle sits atop the ancient walls of the Pisac archaeological park in Cusco, which my family visited every year after they migrated to Lima, the capital.

Ulises Hernandez, an Otomi indigenous man, guardian of native seeds, holds a ” tunicated corn”, one of the oldest varieties. It is believed to be the missing link between the Teocinte (wild ancestor of corn) and domesticated corn. This image represents the missing link of the indigenous peoples’ identity.

A double exposure portrait of Elvia Aguirre Palomino, a singer of the traditional Jarawi, as she performs a song dedicated to the planting of corn. Typically, Jarawi singers perform in groups of two or three, singing in harmony while farmers work the land, blending music and labor in a ritual that fosters both community and the growth of crops.

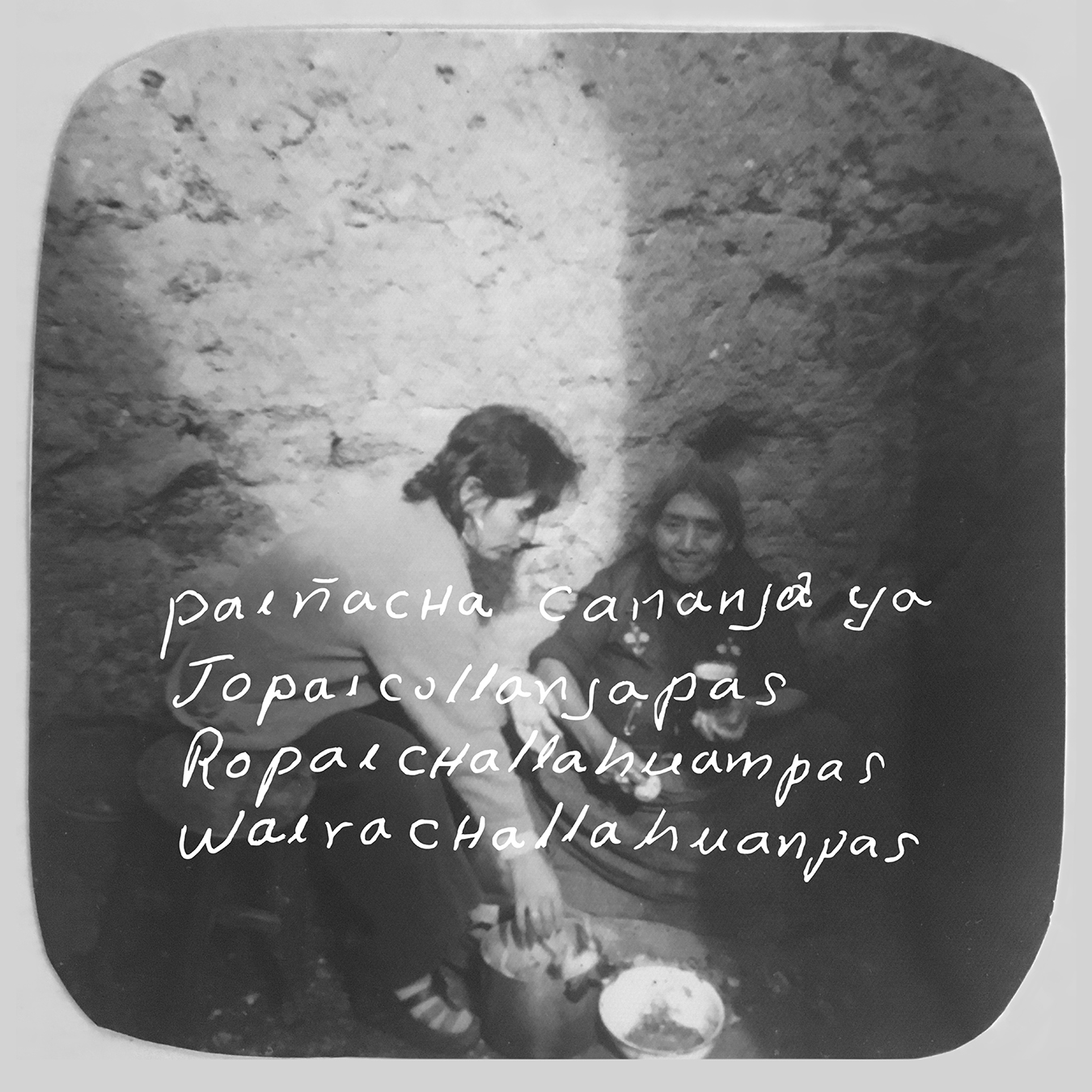

A photograph from my family archive: a portrait of my great-grandmother and grandmother sharing a quiet moment, peeling potatoes inside their adobe house in Cusco. Layered above, as a double exposure, is the transcription of a traditional Jarawi song once sung while planting, a chant entrusting the seed to the Earth.

At night, the wall of the Sacsayhuamán archaeological sanctuary in Cusco. In these sacred places, corn and potato seeds were once adapted to thrive across diverse thermal elevations.

Portrait of Graciela Espinar, a singer of the traditional Jarawi ancestral songs, together with other Wanka indigenous elders, after a corn planting ceremony in Huaylacucho.

A double exposure image of farmers sowing corn while the Jarawi singers perform the ancient verses, in the highlands of Huancavelica, the home land of my grand mother.

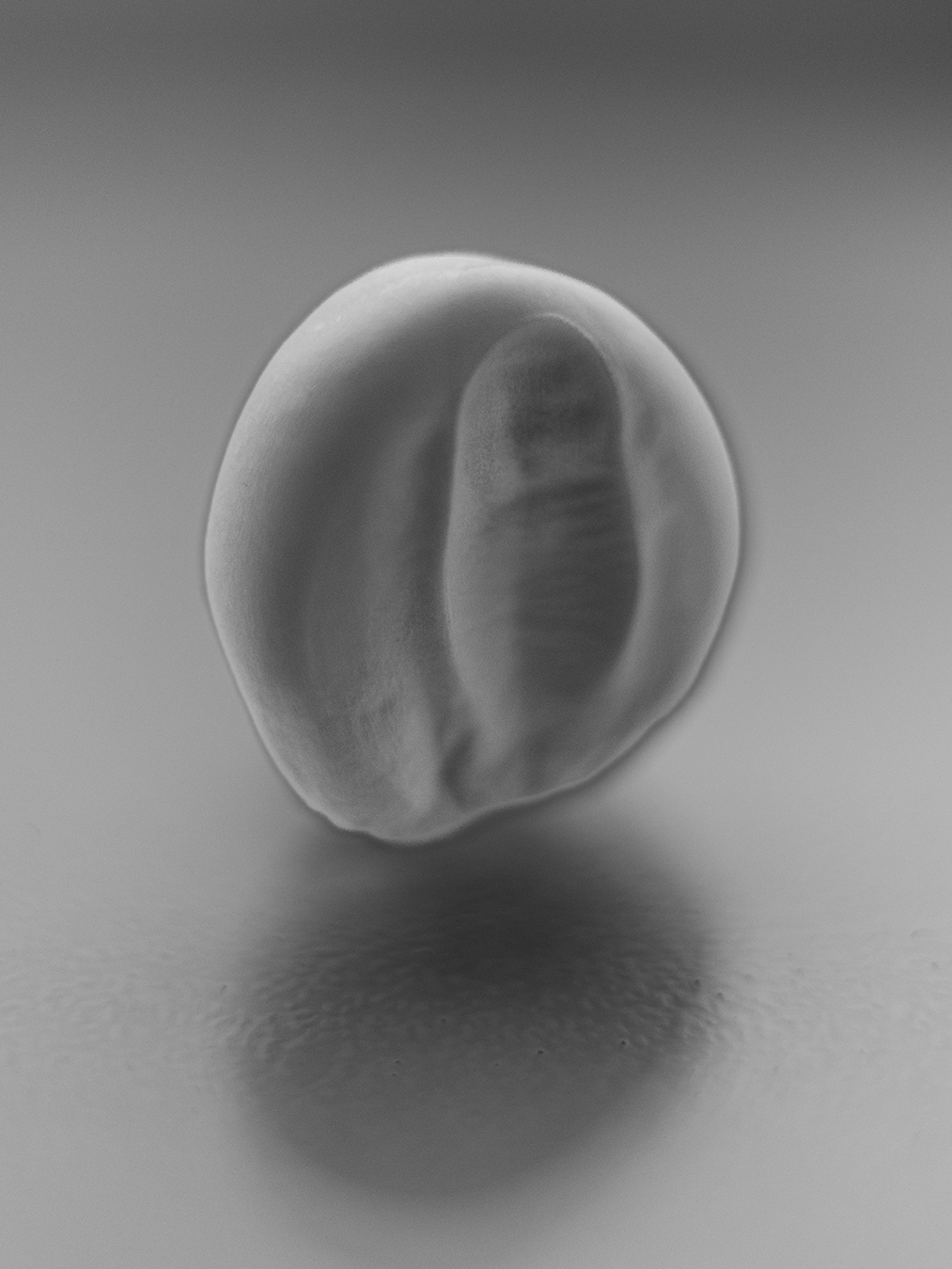

Detail of a white corn seed from the variety known as the White Giant, cultivated exclusively by Quechua communities in the Andes. Reaching up to 15mm in diameter, this remarkable seed retains its size through ancestral rituals and songs performed with profound intention, according to Indigenous farmers.

Victor Vargas, a Quechua-Wari medicine man, performs a healing ritual called “Shokma” using maize flour and rose petals to rub on his patient Daniel. Victor helps him overcome his physical weakness and depression so that Daniel can return to work his fields. According to Quechua-Wari cosmology, corn flour can be used for traditional medicine, rituals and celebrations.