Seconded By: Vladimir Karamazov,

“El Precio de la Tierra” is a 8-year journey covering 20,000 kilometers and 35 mining communities from Peru chronicling the difficult coexistence between Quechua people, their land, and the mining industry. Through the lens of new and old mines, it explores neoliberalism and neocolonialism, showing the fracture of the human relationship with nature and the lack of respect for human rights in the Peruvian countryside.

It all started in 2017, during a work trip to the Sacred Valley of the Incas, when Cinque met a 53-years-old woman who told him that she had fallen ill with a stomach cancer because the water in her village was highly contaminated. For his personal background, Cinque felt deeply connected to this woman’s story and, since that trip, he has not stopped delving into it.

Indigenous Quechua communities living along Peru’s mining corridor endured centuries of discrimination, pollution, and economic stagnation, despite the mineral wealth around them.

Peru has immense mineral wealth in its striking Andes mountains. It’s the world’s No. 2 producer of copper and silver and a key producer of gold. But under its scorching sun, metallic opulence coexists with abject poverty.

Today, the Andes remain home to the country’s poorest indigenous, Quechua-speaking communities whose lands were once sacked by the Spanish and now by multinational companies for metals. The end of colonial rule set up the scene for a new problem: neoliberalism.

The price to pay has been the health of indigenous Peruvians, whose water sources were either diverted to mining or polluted by it. Scores have heavy metals in their blood, causing anemia, respiratory and cardiovascular disease, cancer, and congenital malformations.

Mining has also plundered their wealth by creating dead fields and killing livestock, the engine of the economy for the local population. Moreover, it has reconfigured its relationship with the territory and had a negative impact on the gradual loss of Andean folklore and identity. Andean people have a special connection with Mother Earth (Pachamama) so, with the presence of the mining, their relationship with Pachamama gets out of balance.

Over the years, the project has also been extended to the Andes of Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina and Chile. In this selection of 10 photographs, you will find only the Peruvian chapter.

001_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

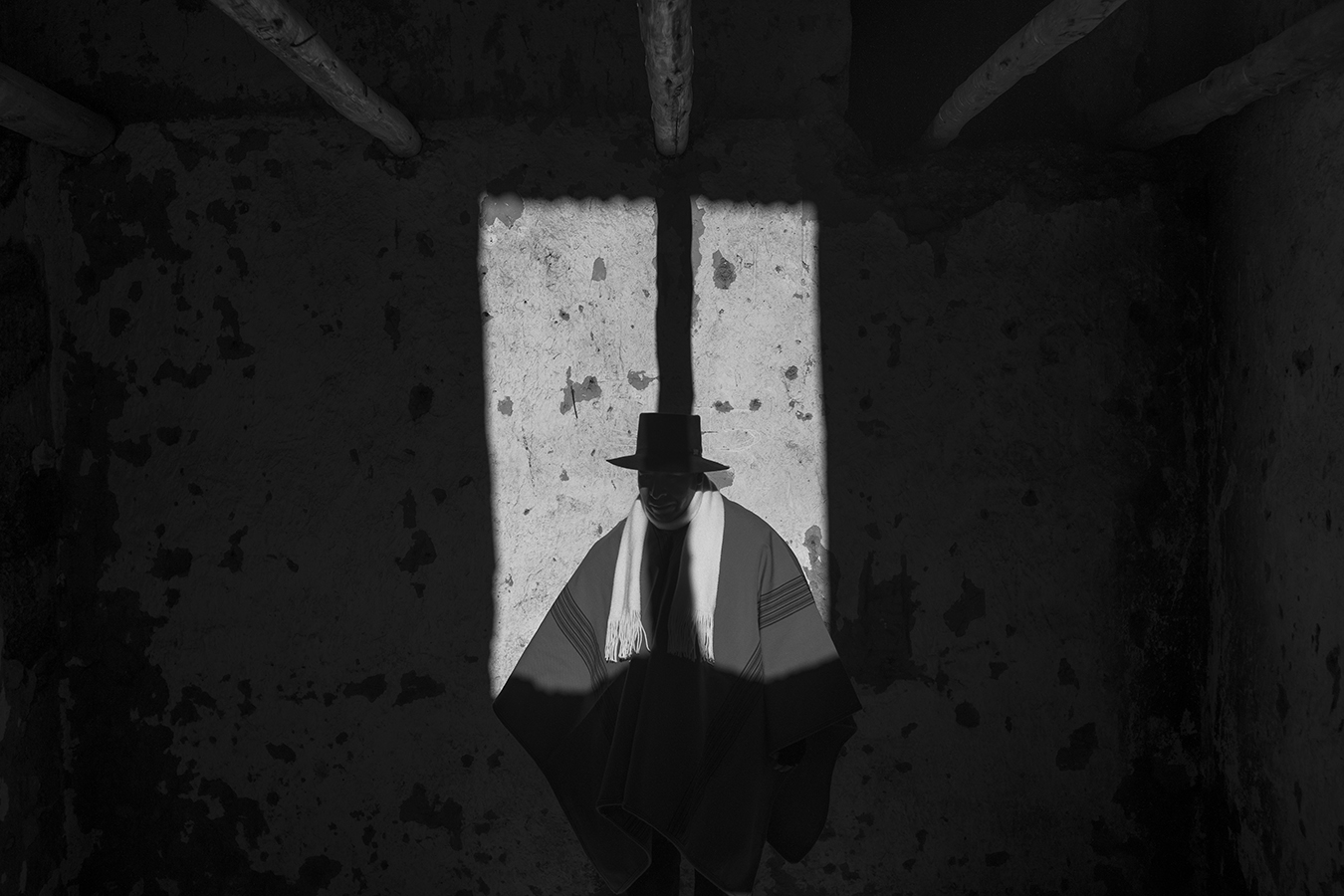

Peru’s indigenous Quechua people have a special connection to the agricultural lands where they and their animals live. The delicate care they devote to agriculture consists of talking to the earth asking for rain and a good harvest. Then, they do a ritual dance to “Pacha-mama,” Quechua for Mother Earth, with passion and grace to express their gratitude. However, where there is mining, agricultural lands and cattle often end up affected by toxic metals such as lead, arsenic, cadmium, and mercury among others, while ancient traditions with the environment slowly disappear.

002_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Drone view of the mining town of Cerro de Pasco

Cerro de Pasco has been a mining town for centuries: once, it offered silver to the Spanish crown, while today it produces zinc and lead. It is located along the Andean cordillera, at 4300 meters above sea level, and it is among the world’s highest cities, but also among the most polluted ones. Its 80,000 inhabitants live around a huge open-cast mine: over a mile long, a half-mile wide, a quarter-mile deep.

Some houses are distant only 5 meters from the sinkhole, while a new mining site is being built a few kilometers away. The water supply of more than 100,000 people is contaminated by the mining waste. In 2012, the Peruvian Ministry of Health declared a state of environmental emergency due to the very high presence of lead in soil, rivers, animal tissue and residents’ blood.

003_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Before the mining company arrived in Ayaviri, Puno, people lived on cheese and milk. Ayaviri’s cheese was exported all over Peru, reaching as far as Lima and Cuzco. Due to water pollution and drought, cows began to produce less milk and milk of lower quality. As a result, the economic conditions of the breeders dropped significantly. Cheese producers now have difficulty selling their products outside the city. People in nearby markets do not want to buy what may be “contaminated cheese”. In the picture, the level of the drought of the land is clear.

004_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

The residents of Ayaviri do not drink the water of their own rivers and lakes because they say it is polluted with mining waste. The pollution has created a cottage industry for water trucks, which charge 25 times the price of water in Lima. According to local people, some neighborhoods only have access to water for 6 hours a week. Water is scarce for the population, while the mining company has access to large amounts of it. As a result, the fields are barren and the few crops that grow are toxic or not enough to sustain families, locals say. Peru’s government has found heavy metals in Ayaviri’s rivers.

005_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Silvia Chilo Choque, 40, bathes her son, 13, with cerebral palsy in Espinar. Water is scarce, so many people collect rainwater during the rainy season to use in baths and other tasks. In the dry season they have no other option but to use contaminated water from the river, boiling it first and then putting chlorine in it. Because this is a long process, often people are only able to shower once a week.

006_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

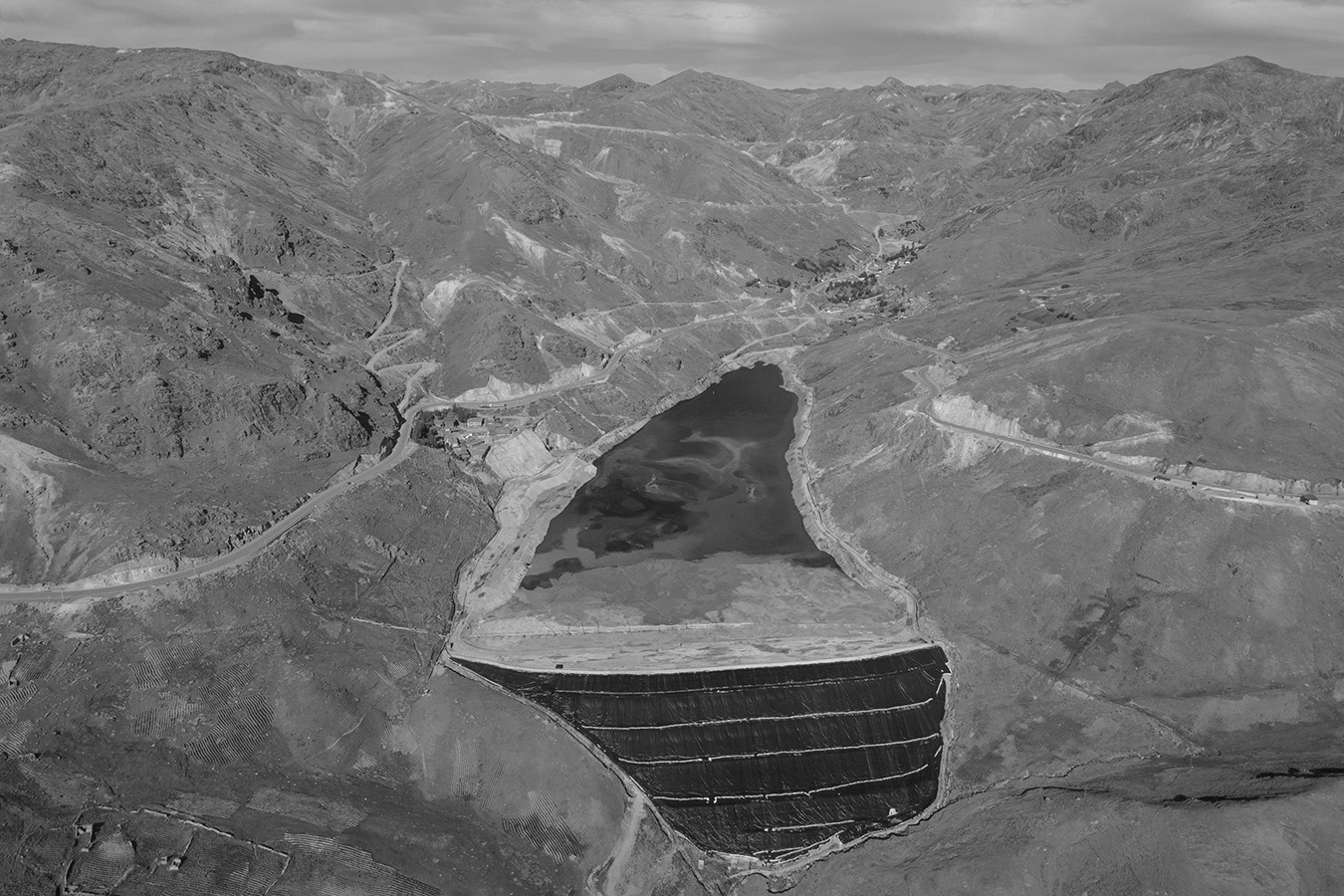

Tailings dam in the rural community of Mimosa, Huancavelica. Mining often generates toxic, liquid waste that needs to be stored and secured with a dam. If the dam breaks or leaks, it can pollute crops and make the water unusable. The indigenous community of Mimosa now lives on the side of the tailings dam, which worries local residents that it could break. Dam tailings leaks are not uncommon in Latin America. The community uses the water from the nearby rivers for drinking, cooking, washing themselves and their clothes, feeding their animals, and irrigating their fields.

007_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Farmers put out a fire in a crop field near Espinar, where 380 hectares burned and 40 families were affected. The problem of fires often afflicts the territories around the city of Espinar and other mining towns, as the fine dust makes the crops more flammable, especially during the dry season that goes from April to October. Lack of water does not make firefighting easier, as people need to rely on blankets, sweaters, and clothes from local farmers to put out the fire.

008_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Grimalda De Cuno in her home in Huisa, Espinar, is commiserating with her stillborn calf, born the day before near the Antapaccay copper mine, owned by Glencore. Because of water is polluted with heavy metals, many animals die from drinking from the river or are stillborn.

Community residents believe that contaminated water from rivers has poisoned and killed their animals. Livestock ha been destroyed over the years, worsening the living conditions of already impoverished farmers and ranchers. In the past 6 years, Grimalda’s family has lost cows, sheep, and llamas. “Mineral content in the water, which is a real problem, is related to the natural presence of these minerals in the soil, and not due to the mining operation,” Antapaccay told Reuters in 2021.

009_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

A group of people work on their potato harvest in the province of Cusco, where mining has affected agricultural production. Potatoes are part of Peru’s tradition and folklore. There are more than 3,000 native potatoes in the country. It is the main source of carbohydrates and almost every household in the Peruvian Andes grows it. In mining towns, as opposed to tourist towns, locals are concerned that potato cultivation is endangered by pollution.

010_El_Precio_de_la_Tierra_Peru

Mernardo Sarabia Flores, 60, president of the Torata Alta Irrigation Commission. Southern Copper operates its Cuajone copper mine near its community in Moquegua, which used to live on agriculture and livestock, especially from the high quality of its avocados, which require a lot of water. In recent years, avocado trees have been dying, affecting the local population’s source of income. Moquegua and much of Peru’s copper-rich Southern region overwhelmingly voted for Pedro Castillo in 2021, who became the country’s first campesino president. But Castillo was impeached and ousted in late 2022 after trying to illegally close Congress. While Castillo’s move was illegal, many in Peru’s South approved of his decision and took to the streets to protest. The country’s military response to the protests left over 60 civilians dead.