Seconded By: Gilles Cargueray,

Fortune, glory and nuggets: the Sahara desert has become a Far West where thousands of young Africans are rushing tempting their fate and aiming a life-changing breakthrough.

A new gold rush, from Sudan to Mauritania, is deeply upsetting the already precarious balance of a region beset by many challenges: military coups, lack of governments, war, trafficking and jihadism.

In this context, in addition to industrial exploitation, artisanal mining centres are multiplying year by year, creating an unprecedented migratory flow of young people who, captivated by the precious metal, have experienced how it could bring a disproportionate wealth in a such a short time.

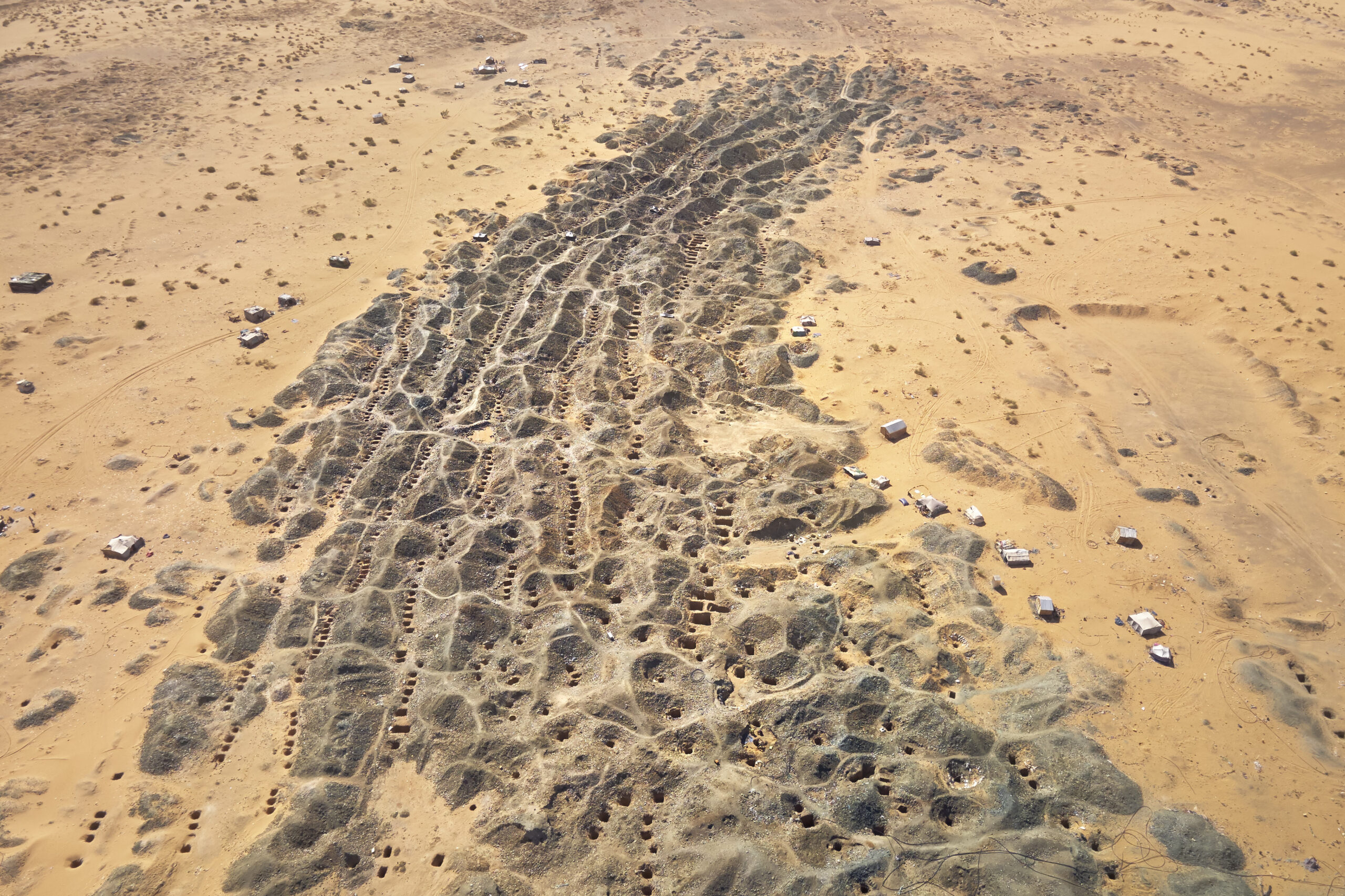

Apart from the sound of the wind, the only audible sound is the one of the generators and jackhammers used along the gold seam to dig tunnels up to 200 metres deep. Real geometries drawn in the expanses of sand, where cases of exploitation, fatal accidents, disputes, theft, and armed attacks are not uncommon.

Few kilometres far from the mining centres, the stones are crushed, sieved and filtered with mercury and cyanide to extract the gold dust, implying a drastic pollution of the groundwater, the sand and all the surrounding areas, where the mercury can be carried by the wind.

Digging and extracting the gold is only the first step of a long, risk-filled journey to process it, transport it and sell it on the black market.

Over one year, along with the journalist Amaury Hauchard we pitched our tent in the middle of the desert to investigate this new gold rush, an important issue for a better comprehension of a region which is becoming the theatre of major geopolitical changes with a relevant impact on the rest of the world.

On the streets of Chami, in Mauritania, a fragment of a poker card turned upside down with a hundred dollar note on the back. Thousands of traditional miners are on their way here to explore the sands of north-eastern Mauritania, since the government opened a new research zone dedicated to artisanal mining in February 2023.

An aerial view of a disused artisanal mining centre in the middle of the Mauritanian desert. The evolution of excavations follows the conformation of the gold seam.

A man starts digging in the desert after having obtained precise coordinates where traces of gold were allegedly found. No one can guarantee the authenticity of the coordinates sold to the orpailleurs, who will have to reach depths of 50-60 metres before evaluating the potential of the pit.

A gold miner poses for a portrait in a safety tunnel at the bottom of a pit some twenty metres down.

With a diameter of about one and a half metres the pits aren’t stable, the strong vibrations caused by the use of the jackhammer can easily provoke the collapse of the rock above. That is why transverse safety tunnels are dug, where miners can take shelter in the event of a collapse and hope for a future rescue.

In the Aïr massif, in northern Niger, a group of miners travel on a truck to return to Agadez.

The tracks connecting the mining sites and the towns where the gold is processed are often frequented by bandits who, taking advantage of a favourable ground, often lead attacks on the convoys.

A group of young people sift the extracted stones transported from the mines to the processing centre, a few kilometres from Arlit in northern Niger. Several young people come here attracted by the opportunity of getting a daily job.

Working conditions are extremely heavy and cases of labour trafficking and slavery have been reported on several gold mining sites.

A young man moves crushed rocks in the Guidan Daka processing centre a few kilometres from Arlit. The resulting powder will be sieved into water where liquid mercury is poured in to attract the gold dust and chemically separate it from the rock.

The high environmental impact dependent on the use of this metal leads to the early development of diseases for those who breathe its vapors, but also for those who are indirectly impacted through contamination of groundwater.

A young man makes gold bars on the market in Agadez, northern Niger. After melting into ingots, the gold is then weighed and according to the density, its carat and thus its price is determined.

Noura Ibrahim at age 19 is already an expert artificier. It is a dangerous job and therefore paid more than others, for 15,000 CFA ( 25 dollars) he goes down into the pits where he places and triggers the dynamite. It is necessary to climb up and out quickly, in a race against time, before the explosion occurs. The expert who taught him the technique died in this way, inside a well; others were injured or lost their hearing.