Seconded By: Lys Arango,

In 2021, the de facto government of Abkhazia region completely banned teaching in Georgian language in schools throughout the occupied Gali district, where most ethnic Georgians reside; Children were wholly transferred to learning in Russian; a mother language turned into a foreign one.

While conquest by armed force is one method of occupation, Russia employs other methods to “Russify” and to homogenize diverse nations that it keeps by force into a singular Russian sphere of influence, controlled by Moscow. Its signature involves erasing national identity, indigenous culture and “rewriting” history. Language, especially critical for small nations like Georgia with a centuries-long history, has been a primary target in Russia’s strategic goals since the 19th century–a systematic approach to cultural assimilation persisting from the suppression of local culture, language in schools, and church services.

This work documents the aftermaths of language suppression and cultural erasure on deeply human relationships, exploring how these actions will impact future connections to the occupied regions, how locals cope with it, and strive to stay connected to their native culture. The historical backdrop, marked by the war in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, initiated by Russian-backed separatists in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali region, sets the stage for the ongoing struggles experienced by the local population. Up to 270,000 Georgians are displaced, 20% of Georgia is under Russian occupation with a constant wave of expelling ethnic Georgians from their homes.

Along with the risk that the Georgian language and culture may disappear from the occupied Abkhazia region, the younger generation is also deprived of their fundamental right to a proper education in their own language in their own country. Locals experience constant psychological fear of surveillance and limitations on freedom of movement and expression. The prohibition extends beyond language, affecting all aspects of Georgian culture and traditions. As the local population grapples with the loss of language and culture, the shown resilience of young students, teachers, and local families becomes an evidence to the enduring spirit of those striving to maintain their unique identity in the face of persistent occupation.

The harsh reality faced by Gali district population today serves as a micromodel of broader patterns of Russian imperialistic strategies observed in various nations and countries.

This work is supported by the Noor Stanley Greene Legacy Prize and the National Geographic Society Explorer Grant.

January 8, 2023. Village Bareti, Kvemo Kartli region, Georgia. The great-grandchild of Mariam Gamkrelidze, a former teacher at the school in the village of Otkhara, Abkhazia region, plays with the ice by the river.

April 30, 2022. Village Jvari, Samegrelo region, Georgia. Women cry at the public funeral of Alika Tsaava, Georgian volunteer fighter killed in Ukraine on April 16. Alika was from the occupied region Abkhazia. During the war in Abkhazia he lost his father, grandfather and uncle. Alika Tsaava was buried with military honor in Zugdidi town.

April 30, 2022. Village Jvari, Samegrelo region, Georgia. People from all over the country gather to pay tribute to the soldier Alika Tsaava, a Georgian volunteer fighter who was killed in Ukraine on April 16. During the war in Abkhazia he lost his father, grandfather and uncle.

January 8, 2023. Village Bareti, Kvemo Kartli region, Georgia. A woman tends to the geese in the village of Bareti, located in the Kvemo Kartli region of southern Georgia. After the war, several families from the Abkhazia region were relocated to the village. Not only is Bareti physically distant from Abkhazia, but it also has a dissimilar climate and natural environment. Unlike the coastal region of occupied Abkhazia, Bareti experiences a harsh winter that persists into late spring, transforming its landscapes into snow-covered steppes.

December 16, 2022. Zugdidi, Samegrelo region, Georgia. A girl stands by the board during her math class at N12 Public School in Abkhazia, located in Zugdidi. The majority of students in the school come from families who fled Abkhazia during the 90s. However, there are also students whose parents moved from the occupied Gali district to the Georgian-controlled territory because they wanted their children to be educated in Georgian. This situation highlights the dual challenge these students face. Not only is there the danger of the Georgian language disappearing, but there is also a significant issue regarding the right to receive a full-fledged education—a fundamental human right. Without knowledge of the Russian language, children find it challenging to learn subjects like math and physics, limiting their ability to fully express their potential. Before attending the class, I interviewed school director, informed her fully about the content and aim of the work, and, with her consent, was allowed to photograph.

December 15, 2022. Zugdidi, Samegerlo region, Georgia. Mzevinar Gelantia, the director of Public School N11 of Abkhazia named after Ilya Vekua. She resided in the Gali region and was compelled to leave her home and school when the war erupted. However, in 1993, she made the decision to return to her village and embark on the gradual process of rebuilding the school alongside several other women. They established the school in a hidden house that belonged to a family who had fled the region. The school was located approximately 12 kilometers away from Mzevinar’s residence, which meant she had to leave her village at 6 o’clock every morning to reach the school. Mzevinar wholeheartedly managed the school from January 1994 until May 1998. During their time at the school, there were instances when helicopters would land, prompting Mzevinar and the other teachers to quickly ensure the safety of the children by discreetly hiding them among the nearby bushes. As Mzevinar explains, their responsibilities went beyond protecting the children’s lives; they also aimed to safeguard their spirits’ freedom. They firmly believed that open communication in the Georgian language would foster a sense of independence and liberate their souls without any constraints.

July 29, 2022. Village Khurcha, Samegrelo region. Georgia. Children swim in the Enguri River in Khurcha Village. Prior to 2017, there was a Khurcha-Nabakevi checkpoint. In 2016, Giga Otkhozoria, an internally displaced person (IDP) from the Gali district, was killed there. Otkhozoria was attempting to transport food into the breakaway Abkhazia region for a funeral ceremony for his aunt on May 19, 2016, when the so-called border guards demanded payment in exchange for allowing him to transport the goods, leading to a dispute. Otkhozoria was on Georgian-controlled territory when he was shot six times by the so-called border guard.

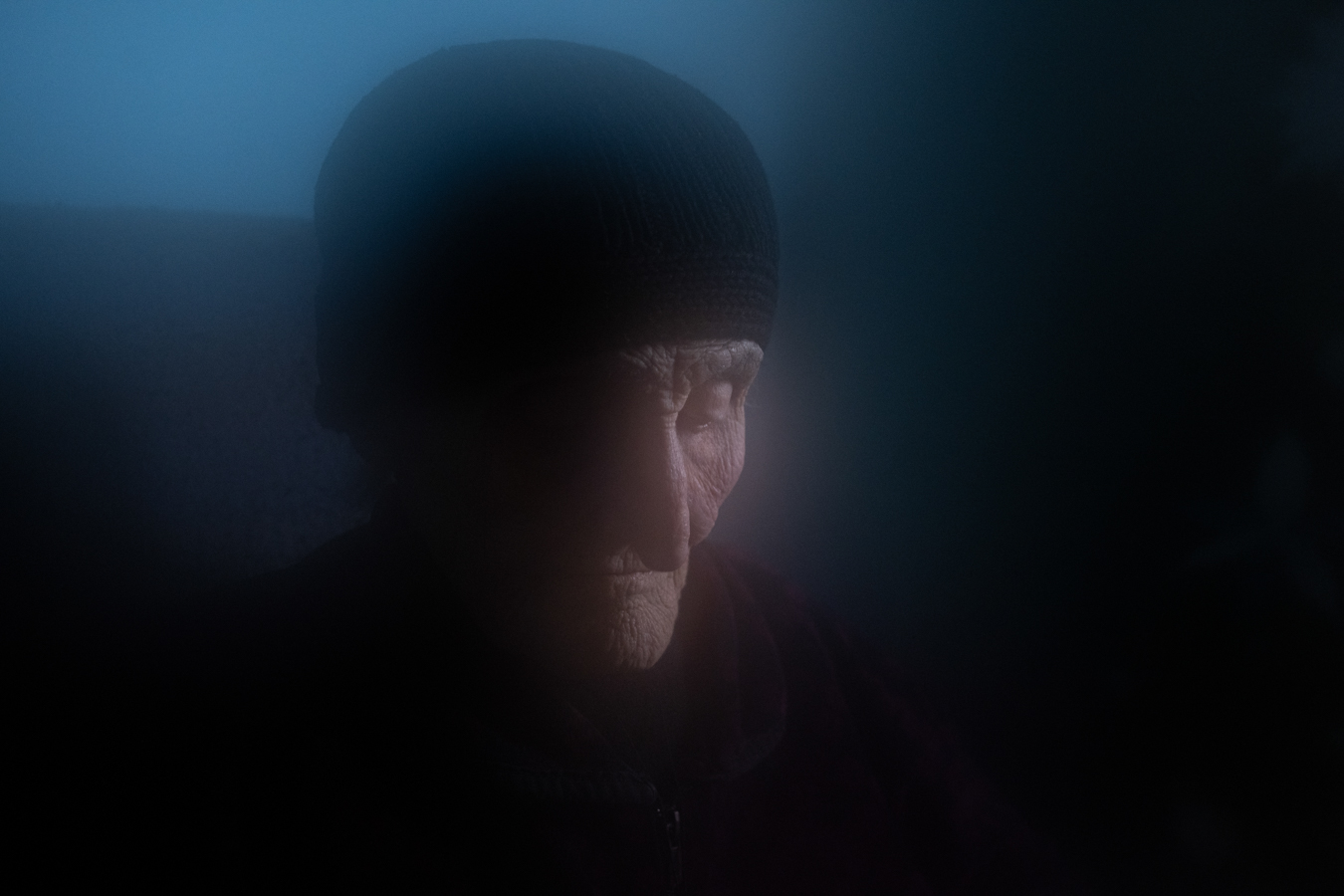

January 8, 2023. Village Bareti, Kvemo Kartli region, Georgia. Mariam Gamkrelidze sits in her living room in the village of Bareti. She used to be a teacher in the village of Otkhara in the occupied Abkhazia region. At that time, they never thought that war would unfold, forcing them to leave their homes. She misses her Abkhazian and Georgian neighbors dearly.

December 10, 2022. Zugdidi, Samegrelo region, Georgia. Nini (name changed for safety reasons) covers her face with a large leaf. Today, she studies at a university in the Georgian-controlled territory. She chose to stay in the Samegrelo region, which borders the occupied Abkhazia region, to be closer to her family. She recalls when she first crossed the Enguri bridge, she didn’t talk much, always fearing punishment or detention for speaking in Georgian. Over time, she has grown accustomed to it and feels safer now. It was also common for them to be denied permission to leave on the day of an exam, forcing them to navigate through the woods and cross rivers under a constant state of fear of detention. Additionally, she recollects an incident at a checkpoint while visiting her parents, where the border official insisted, she speak in Russian, asserting that it is her native language. He suggested that if she preferred not to, she should return to where she came from.

April 30, 2023. Village Muzhava, Samegrelo region, Georgia. The young members of the ‘Sama’ ensemble are photographed during a rehearsal at the Muzhava village dance studio, situated beside the occupied Abkhazia region. Almost 80% of these ensemble members come from families displaced due to the war in Abkhazia. Giorgi Matua, the ensemble’s founder, teaches Georgian traditional dances to most of them for free. Performing Georgian dances publicly is not permitted in the breakaway region of Abkhazia. Before attending the class, I interviewed ensemble’s founder and teacher, informed him fully about the content and aim of the work, and, with his consent, was allowed to photograph.