Seconded By: Tim Smith,

The Gran Chaco, one of the planet’s largest and most endangered dry forests, is vanishing

at an alarming rate. Bulldozers carve roads into its heart, clearing land for agriculture and

silencing one of South America's most overlooked ecosystems. Rich in biodiversity and

vital for climate balance, the Chaco teeters on the brink—its fate hanging in the balance.

Amid this unfolding environmental crisis, an unlikely group of environmental protectors has

emerged: the beekeepers.

For communities like Sauzalito, beekeeping isn’t just a way to make a living—it’s a form of

resistance, a declaration of care for the land. “Where there are beekeepers, not a single

tree is cut down,” says Luchy Romero, a local beekeeper. Their hives rely on the native

forest’s flowering trees and plants. If the forest disappears, so do the bees—and so does

the livelihood of those who depend on them.

These beekeepers are doing more than harvesting honey. They are safeguarding a living

forest, tree by tree, hive by hive.

But this local fight reflects a deeper, global emergency. Bees around the world are

vanishing—victims of habitat loss, pesticides, and industrial farming. Without them, crops

fail, ecosystems unravel, and food systems falter. Protecting pollinators isn’t just a rural

concern, it’s a global necessity.

Now, even more threats loom. Weakening Argentina’s Forest Law could open the

floodgates to accelerated deforestation, stripping away the trees beekeepers rely on.

Meanwhile, synthetic honey floods international markets, undercutting prices and

devaluing the raw, forest-born honey these communities produce. In this climate, organic

certification is more than a label—it’s a lifeline, ensuring both economic survival and

ecological integrity.

This is a story not just of loss, but of hope. A blueprint for how food production can

regenerate nature instead of destroying it. A vision of coexistence, where people and

forests thrive together.

The choice is ours: continue down a path of destruction, or support those working at the

frontlines of regeneration—before it’s too late.

Beneath the Veil of Smoke: The Beekeeper Who Sparked a Movement

Rosa Ceballos, the first female beekeeper in El Espinillo, Chaco, stands enveloped in smoke from the hive. A decade ago, she broke local gender norms and inspired a generation of women to pursue economic independence through beekeeping.

In the Archives, a Queen Remembered

A 19th-century French bee model, donated in 1890 to the University of Buenos Aires, still adored by the community but resting in the beekeeping faculty’s archives. Before Africanized bees arrived in Latin America, biology education in Argentina followed the French academic model.

Where the Nectar Grows, the Forest Stays

Luchy and Ely Romero inspect one of their hives in El Sauzalito, in Argentina’s remote Impenetrable dry forest. Luchy is a leader of the local beekeeping cooperative, which includes 63 Criollo and Indigenous families. Through honey production, they’ve found a sustainable alternative to deforestation and migration. “Where there are beekeepers, no trees are cut—because without trees, there are no flowers, and without flowers, no nectar.”

The Blond Sentinel of the Living Tree

A Melipona bee—stingless and native to the region—guards the entrance of its hive, built inside a living tree. Known locally as rubiecita (“the blond one”), this species produces just one kilogram of honey per year. Valued not only for its sweetness but also for its medicinal properties, its honey holds deep cultural and spiritual meaning for many Indigenous communities in the Gran Chaco.

Ancestral Harvest in the Shade of the Forest

Esteban, from the Algarrobal community in northern Chaco, uses an axe to extract a hive of native bees known as “Corta pelo” named for their habit of biting hair when they attack. In both the Qom and Wichí communities, harvesting honey from the forest is an ancestral practice done for personal consumption. The honey comes from feral or native bees.

With Every Hive, a Tree Spared

A Wild bee colony clusters at the hive entrance to protect their queen, after the honey is collected by the members of the Wichi community who venture into the forest to gather honey as part of their ancestral hunter-gatherer traditions. The activity strengthens community bonds and preserves traditional ecological knowledge.

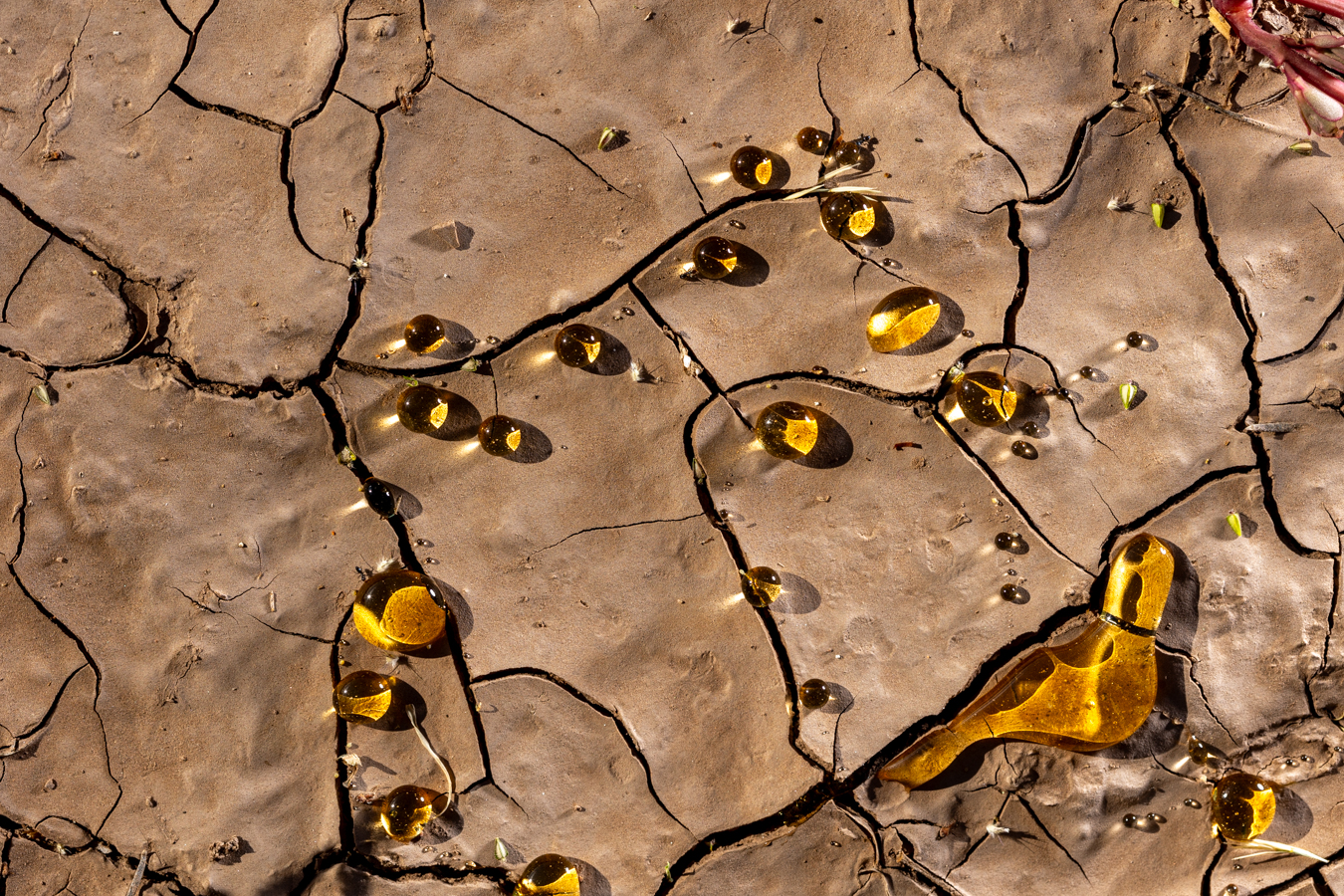

Drops of Hope in a Dry Land

Drops of honey fall onto the dry, cracked earth of the Argentine Chaco. The Chaco is one of the world’s most overlooked ecoregions, facing some of the highest rates of deforestation globally. Its hardwood is exported internationally, while its land is exploited for industrial agriculture. This deforestation is happening at a rapid pace, with significant consequences for biodiversity and the climate. Honey production could be the saviour.

Climate, Bees, and the Fight to Sustain the Chaco

Ely Romero prepares for the last honey harvest of the year at one of his apiaries on the outskirts of El Sauzalito, deep in the Impenetrable forest of the Chaco region. “Impenetrable” is the Spanish name given to this territory because of its difficult access and dense vegetation. In recent years, many hives have been lost due to extreme heat and drought, consequences of the climate crisis affecting this unique ecoregion.

Liquid Gold from the Chaco

A toast with honey. Argentina is the world’s third-largest honey exporter, with the U.S. and Europe as its main markets. The Argentine Chaco is one of the few regions globally producing certified organic honey from native forest. While most honey is exported in bulk and blended—losing its unique flavors—locally it’s cherished as a natural sweetener and remedy. Each honey reflects the unique flora of its origin, offering a taste of its native landscape. Supporting local honey helps us value and protect these ecosystems.

Where the Community Leads

The Wichi community of Victoria Este, in Argentina’s Salteño Chaco, comes together in traditional circle gatherings to openly discuss the challenges facing their people. This cultural practice defies Western ideas of leadership by prioritizing collective wisdom and community over individual authority. From the ground, not the top — the Wichí model of Governance, to build a fair future together.