Seconded By: Lys Arango,

This project explores how individuals use sacred religious texts especially the Quran to preserve personal memories and cultural heritage. At the heart of the story is my grandfather, Abdulredha Dhiaa Al-Deen, born in 1933 in Karbala, Iraq. Over the course of his life, he witnessed major historical turning points: World War II, the fall of the monarchy, the rise of the Ba’ath Party, the 1977 Safar Uprising, the 1991 Intifada, and the 2003 Battle of Karbala.

My grandfather isn’t a trained historian or archivist. His education began with a local mullah, learning to read and recite the Quran a timeless book that, to him, never grows old. He often quotes:

“Indeed, it is We who sent down the Qur’ān, and indeed, We will be its guardian.” (Surat Al-Hijr, verse 9)

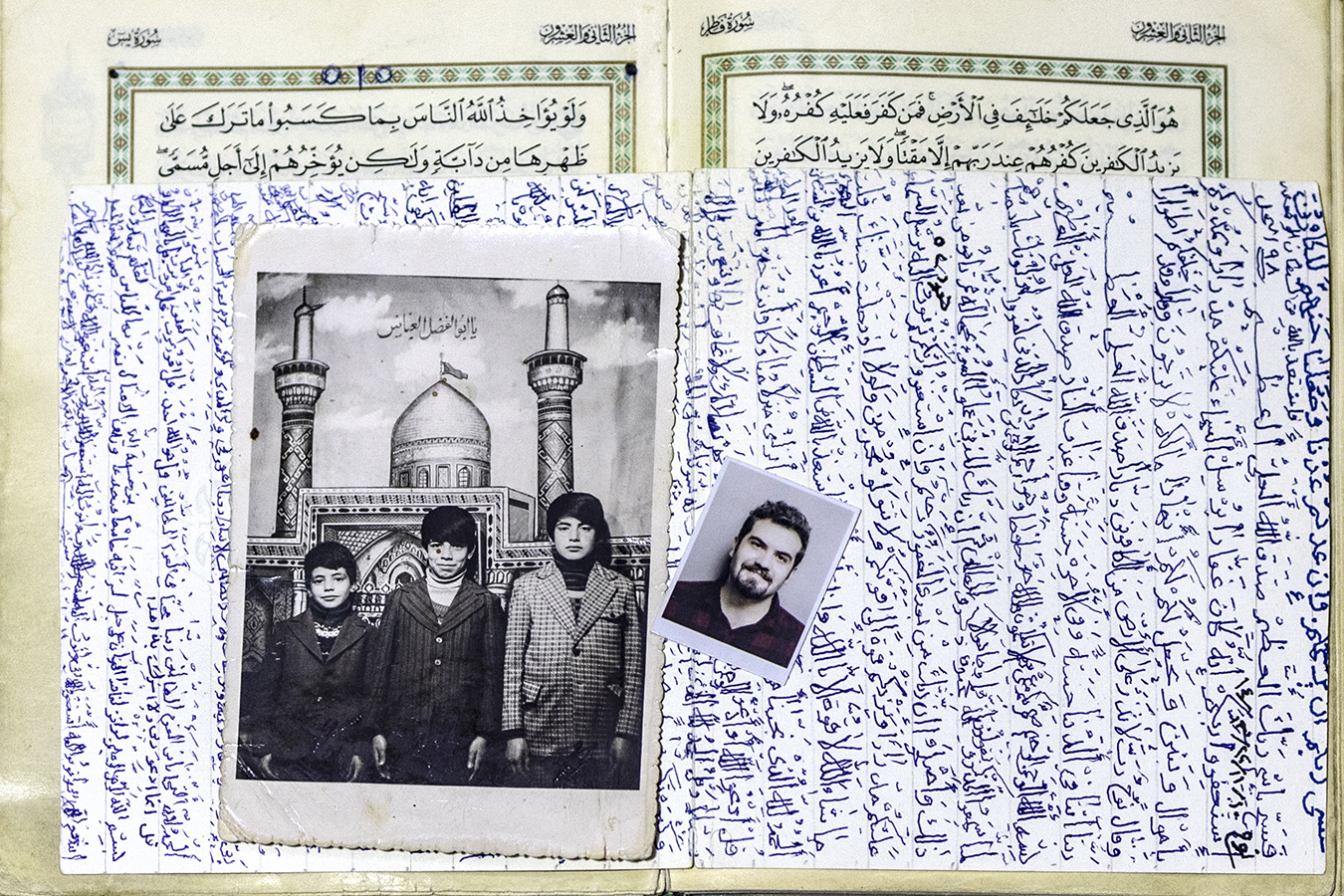

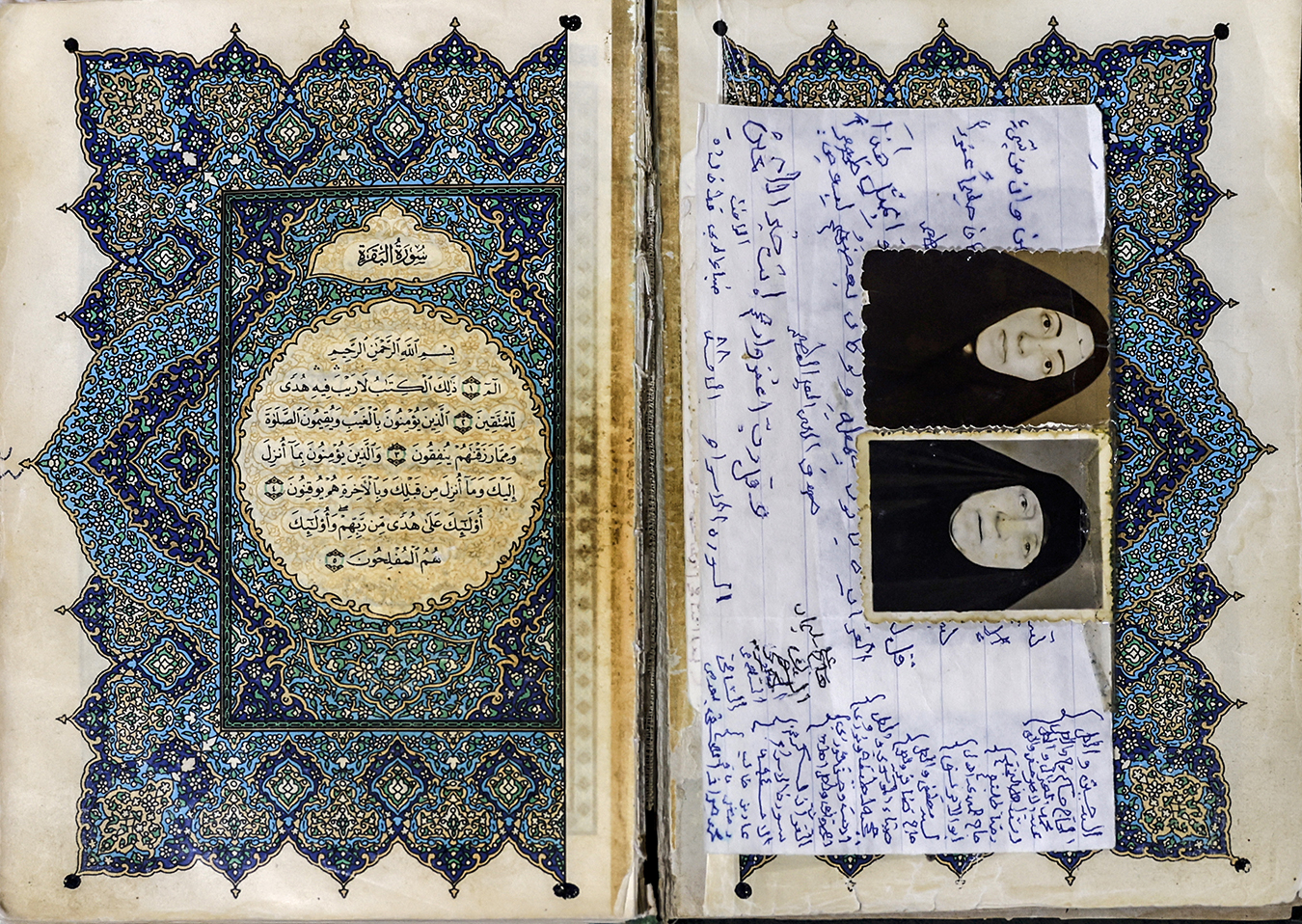

What makes his relationship with the Quran unique is how he turned its margins into a living archive. In between sacred verses, he documented family memories, the transformation of his neighborhood, and reflections on a city he’s watched slowly vanish before his eyes.

He won’t let me take notes. Instead, he shows me photos and tells me stories like the first time he heard a radio playing in a café on Abbas Street. Today, that street is in ruins, and its historic buildings have been demolished in the name of religious expansion and modernization.

“They’ve destroyed Karbala,” he tells me. “It doesn’t exist anymore.”

Through his Quran, a sacred and static text becomes a memorial, a vessel for memory. His handwritten annotations tucked among the verses are fragments of a lost city. The Quran becomes both a personal and collective archive. The photographs I make aren’t just visual records they are sacred relics in their own right. Even I born and raised here barely recognize my own city anymore.

The project also reflects on the rituals of Ashura in Karbala, as told to me by my grandfather. Each year, the first ten days of Muharram carry deep spiritual weight, especially among Shi’a Muslims, who commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), in the Battle of Karbala.

As the month begins, the city transforms. The red flags atop the shrines are replaced with black ones a symbol of mourning. Wooden structures called takaya are built near the shrines, topped with 72 colored glass lanterns representing Imam Hussein’s companions. These structures, rooted in Karbala’s Ottoman past, serve as spiritual and social gathering points in the city’s old neighborhoods.

On the second of Muharram, the historic Haydariyya procession established in 1880 reenacts Imam Hussein’s arrival in Karbala. When the procession passes by the takaya, their curtains are lifted and the voice of the iconic radoud(mourning reciter) Hamza Al-Saghir echoes through the streets.

When my grandfather hears his voice, he says, “This is how we recover our memory.”

The lanterns stay lit until the night of the ninth.

Each evening, mourning processions take over the streets, led by an iron torch shaped like a boat called al-Mash’al, illuminated with 72 lights. At dawn on the tenth day, the takaya lanterns are extinguished and taken down marking the martyrdom of Hussein’s companions. The rituals culminate in the Tuwairij Run, a mass mourning march dating back to the 19th century.

Despite the changing skyline of Karbala with shrines expanded and old neighborhoods erased these rituals remain deeply rooted in the city’s spirit. The physical landscape may fade, but its spiritual memory lives on.

Through this work, I hope to illuminate the fragile yet resilient connection between sacred text, personal memory, and public history. My grandfather’s Quran stands as a witness—as both a holy book and a living archive—reminding us that engagement with the sacred isn’t only about worship, but also about preservation, storytelling, and personal testimony of history.

My grandfather, Abdulredha, keeps a photo of me along with picture of my father and uncles inside his personal Quran. He told me he keeps them there to remember me in his daily prayers as he reads the Quran, especially since I moved from Karbala to Baghdad on 2020

My grandfather, Abdulredha, keeps a photo of his mother and sister at the beginning of his personal Quran, which he inherited from his mother. He told me he places their photo there because they were the beginning of his life just as these are the very first two verses of the Quran.

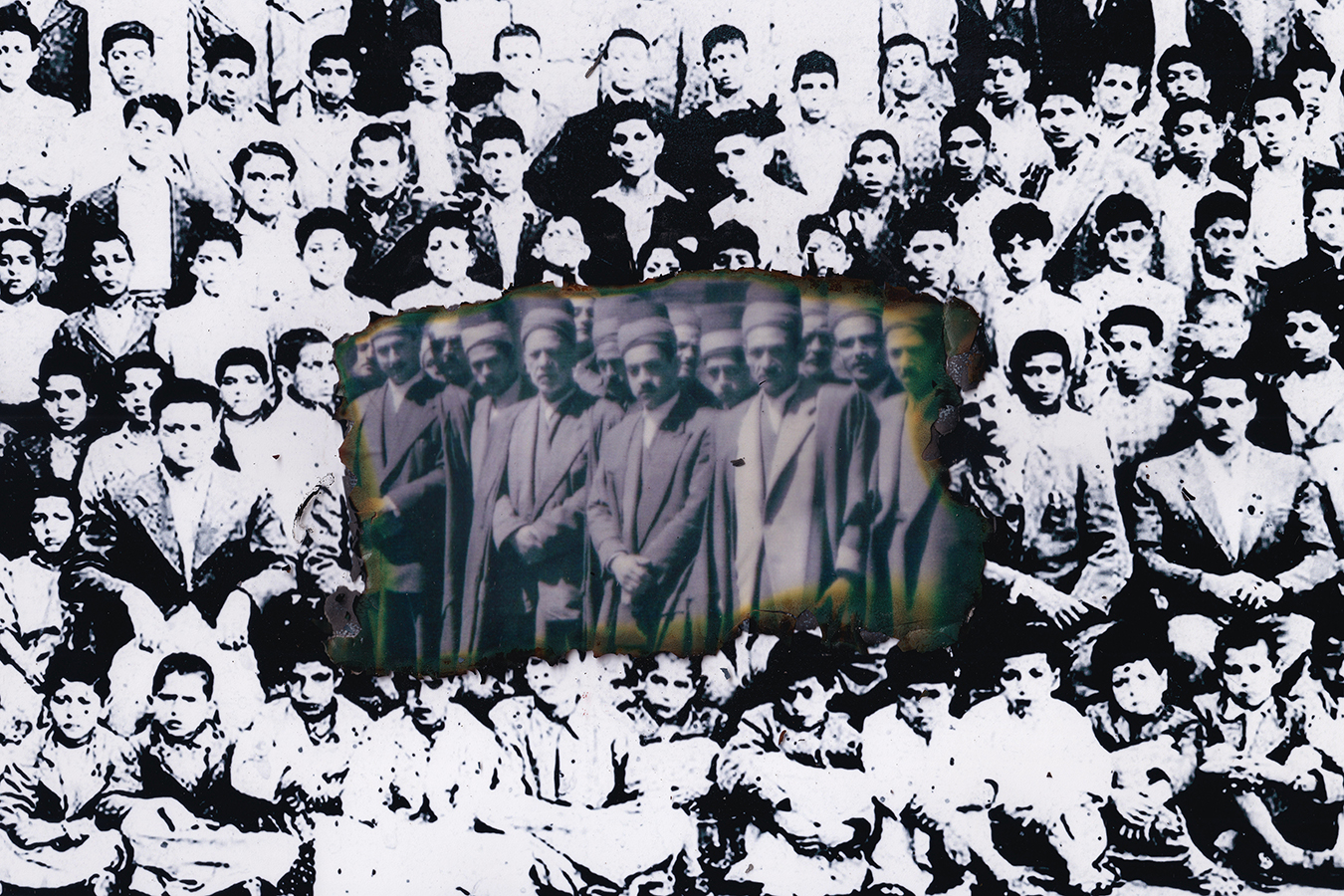

A photo shows my grandfather, Abdulredha, during his school days. He learned to read and write through the Quran, which is why he considers it a lifelong companion. In the background, a group of students can be seen. I found the worn-out photo hanging in a traditional café in the old city of Karbala.

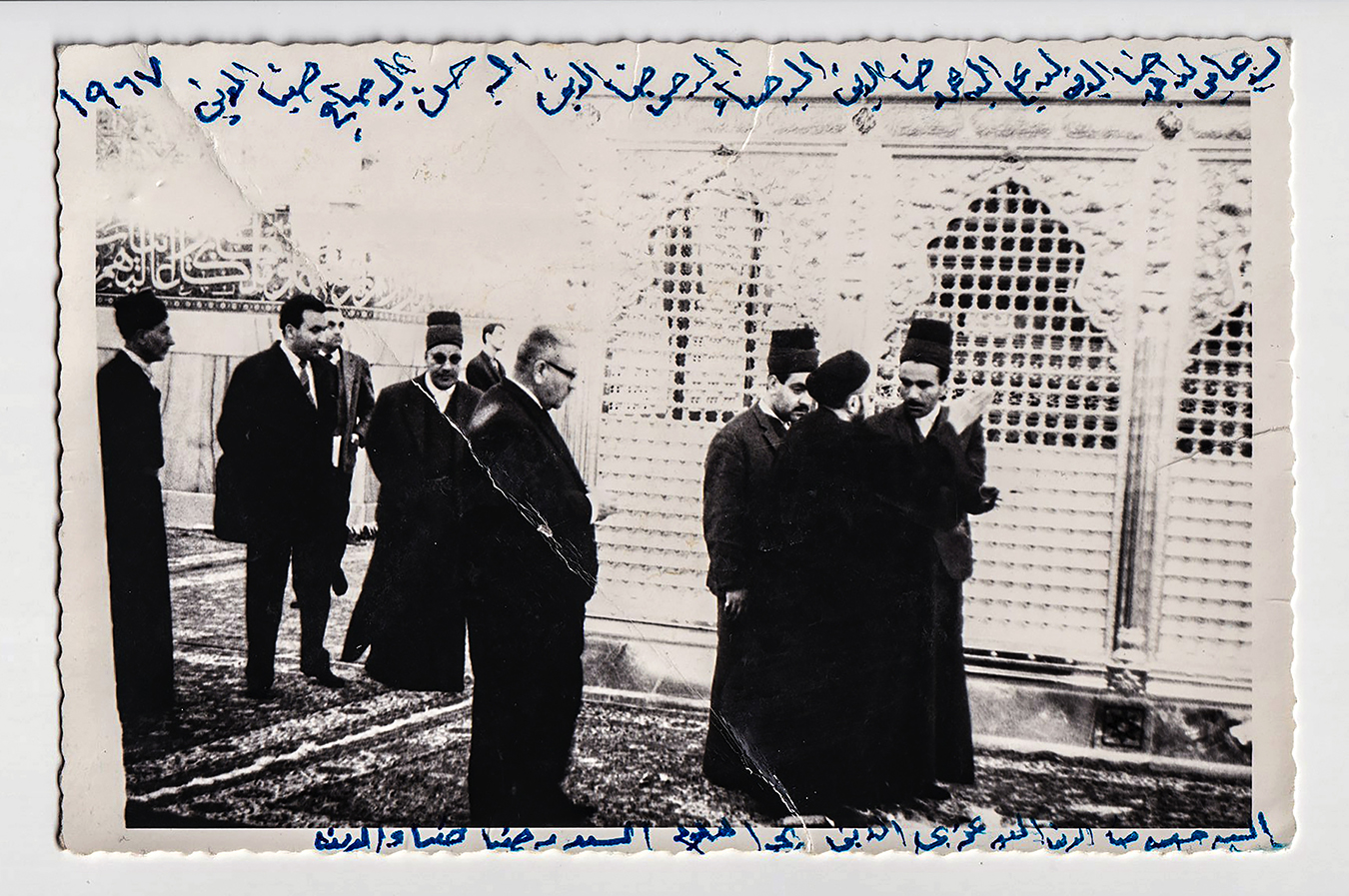

A group of men known as Sadah al-Khidam (the serving descendants of the Prophet) appear during a mourning procession in Karbala during the days of Ashura. My grandfather asked me to attend this procession, saying it is part of our family’s heritage. Everyone wears the traditional attire associated with the Sadah, preserving a long-standing cultural and spiritual tradition.

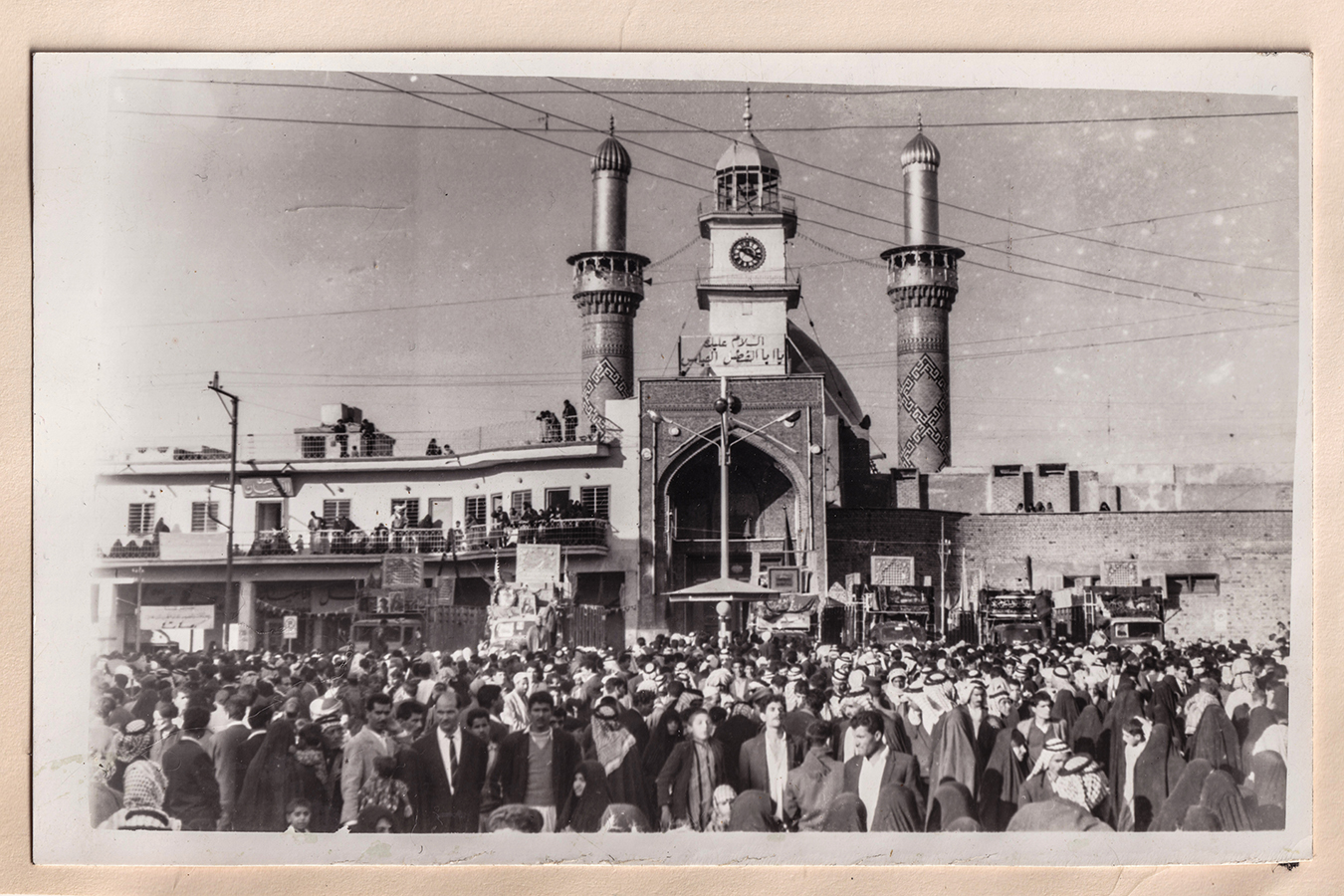

The photo shows the shrine of Imam al-Abbas in Karbala, taken in 1965. I found it in my family’s personal archive.

A photo of Karbala from the 1970s is displayed on the screen of an old television, showing the shrines of Imam Hussein and Imam al-Abbas during that era. My grandfather told me that the first time he ever listened to the radio was in the 1940s, when he was a child. He was with his father at a traditional café in Karbala, and at the time, he genuinely believed there was a person inside the radio speaking to them.

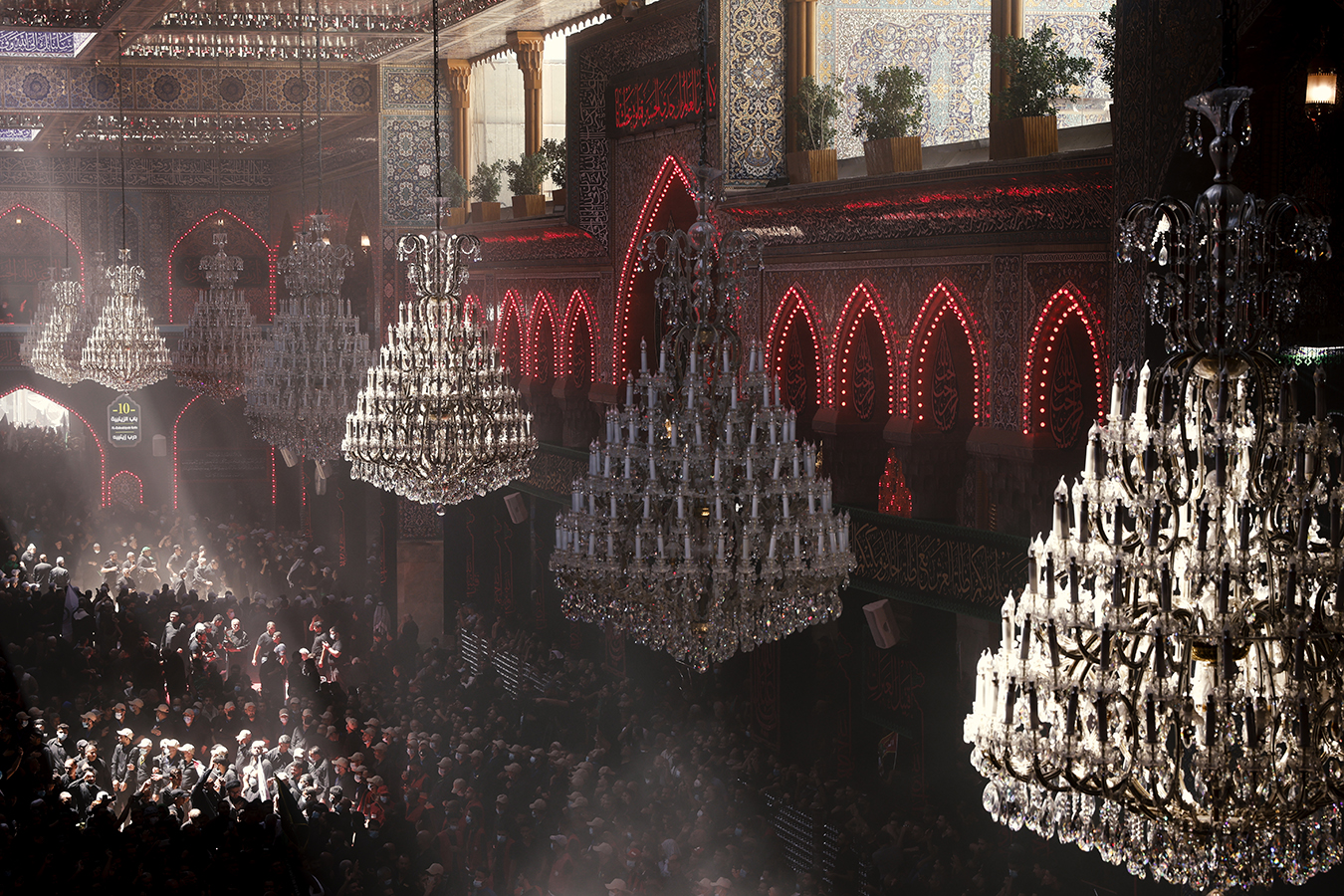

Shi’ite Muslim pilgrims gather to commemorate Ashura, the holiest day on the Shi’ite Muslim calendar in Karbala, Iraq

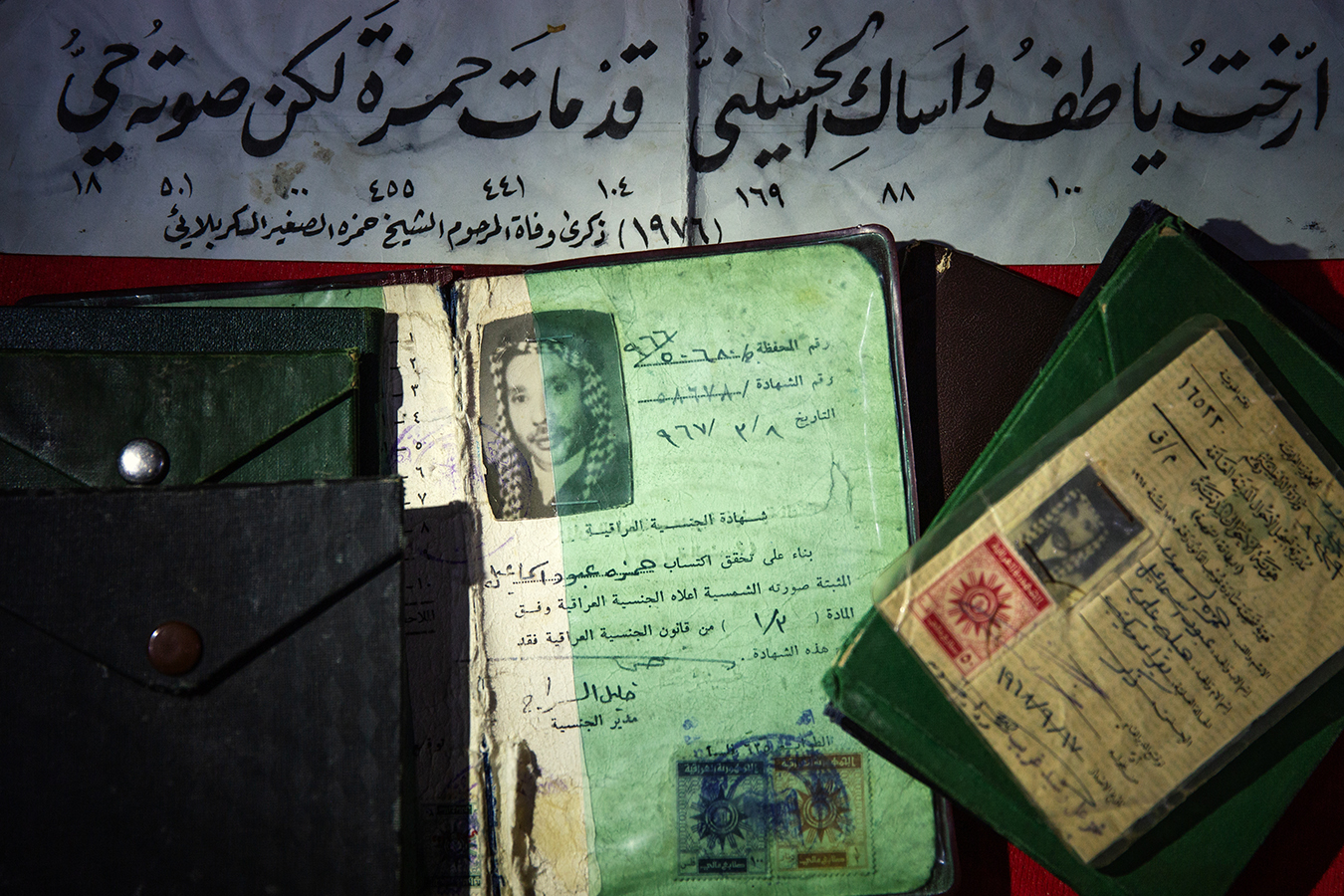

The image shows a collection of documents belonging to Hamza Al-Sagheer, presented to me by his son, Ahmed. At the bottom, his Iraqi nationality certificate appears beneath a handwritten note that reads, “Hamza is gone, but his voice lives on” a tribute written by a friend in memory of his passing.

Hamza Al-Sagheer (1921–1976) was one of Iraq’s most beloved and influential Hussaini reciters. Born in Karbala, he became known for his powerful, sorrowful voice and his deeply emotional renditions of the Karbala tragedy. His performances were a central part of the Ashura rituals in Iraq, and his legacy continues to resonate through recordings still played today and the generations of reciters he inspired.

As my grandfather Abdul Redha once told me, “When we open the tekkiyeh in Ashura and play Hamza Al-Sagheer’s voice, this is how our memories return.”